Reading is Writing #7: Headshot

Rita Bullwinkel plays with her food. Also, Tariffs? Gorbachev?

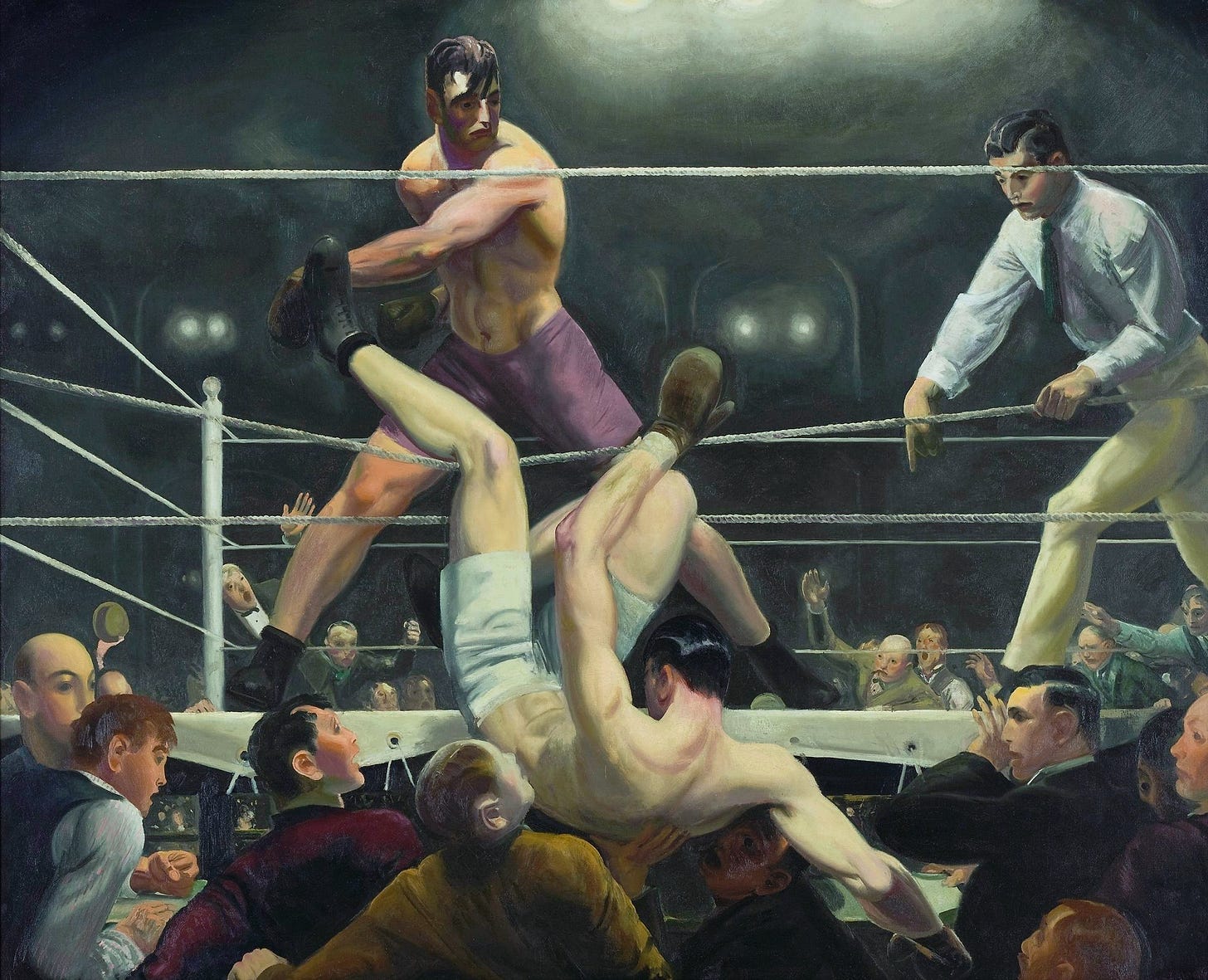

Rita Bullwinkel’s 2024 novel Headshot tracks eight adolescent boxers across a two day youth women’s boxing tournament in Reno, NV. It’s a short, quick moving novel that does some interesting things with imagery and tension. One of those things is a sort of linkage between food/eating and bodily failure that structures what Bullwinkel thinks makes for a good boxer: An almost anti-material level of psychological control and discipline, disembodiment as embodiment.

But before the book stuff, I have to address an influx of new subscribers who found this newsletter thanks to a viral Tik Tok about Collapse by Vladislav Zubok. That video was explicitly political. In it I argued that the proper frame for what was happening in the U.S. was not a classical fascist moment, but the application of capitalist shock therapy of the sort unleashed by the U.S. against the Warsaw Pact during the latter’s disintegration. The American oligarchy, or one faction of it, is using an economic crisis to reassert control of society, the same way they’re using a manufactured crisis of state legitimacy to purge the public service and privatize essential functions of government.

None of this is particularly original to me. Writers like Yasha Levine and Evgenia Kovda, and podcasters like Mark Ames and John Dolan, have been making this point for months, if not years, while Adam Curtis made a documentary predicting something like this almost a decade ago. Curtis Yarvin, an important ideologue of the tech faction within the American regime, has been open about, and supportive of, this shock therapy for quite some time. Anyone who has read Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein can see what’s happening.

That said, I appreciate that so many of you—at this point an outright majority of subscribers—took the time to come sign up for my little literary newsletter. I am very, very humbled that so many of you, from so many places (64 countries!!! But somehow not Rhode Island?), have signed up to read this blog.

I don’t want you to get the wrong idea about what this newsletter is and what it does, so I’ll lay that out right now:

This newsletter is a project to document the intellectual labor that goes into getting a Master’s of Fine Arts in Creative Writing (Fiction), because I believe a literary education should be free, democratic and universally available. It mostly discusses the literary criticism aspect of things, since, as the headline to this piece says, Reading is Writing.

This newsletter occasionally comments on the political valence of movies and books. All art is political and all criticism is political. While I have strong political opinions, I am not a political commentator or organizer and this newsletter is not and (god willing) never will be about formal politics.* I am an amateur literary critic, not a political strategist.

However, I publish about 2-3 pieces of straight up literary criticism and 1-2 pieces of more expansive theorizing/political criticism each month. If you came for the politics, I hope you will stay for the graduate level English homework. There’s enough things in fiction to make it worth your while.

The core of this project will always be free. I will turn on paid subscriptions at 1,000 free subscribers, or in early June, when I go back to Bennington, whichever comes first, and I will then post (occasional) subscriber-only content.

Enough people asked me directly what I think people ought to do about the present crisis that I feel they deserve an on-the-record response. If you are an American, I think that, if you are not already, you should get involved with Palestine solidarity activism; the Palestinian cause is where the fight for American political liberty is hottest. It is the point of decision in this battle.

Just as Palestine is itself the laboratory for the methods of war that the great powers will find acceptable in the 21st century—summary executions, indiscriminate bombardment of civilians, starvation, genocide, systematic use of sexual violence—so too is the U.S. response to it a laboratory for the techniques of repression that will be unleashed against dissent in so-called democratic societies. The Department of Homeland Security has announced it will surveil immigrants’ social media accounts for criticism of Israel, which the American government considers antisemitic (when, in fact, it is rank antisemitism to conflate political disagreement with Israel with discrimination against Jewish people). The whole force of Silicon Valley is bent on producing new technologies to create the sort of fantasies that feed into this brutality.

Further, Israel is a profoundly unequal society, as Perry Anderson has written; as Prussia was once an Army with a state, so is Israel a military industrial complex with a state. That Israel solves its balance of payments problems by selling high tech industrial goods and weapons and repressing domestic consumption is a possible model for the U.S. post-tariff shock: A society of bullets, nominally governed by the ballot.

Rümeysa Öztürk is facing deportation for writing for a newspaper I used to edit. Mahmoud Khalil is facing deportation for protesting his university’s involvement in the slaughter of his people. Grant Miner, President of UAW Local 2710, and a Jewish student, was fired and expelled by Columbia University for his solidarity with Khalil and with the Palestinian cause. The attack on Palestine is an attack on immigrants, it is an attack on workers, it is an attack on the existence of a democratic society.

I’m barred by conditions of employment from saying more explicitly what I think individuals should do in this political situation. But if you listen to Fragile Juggernaut: What Was the CIO? by Haymarket Books you’ll get some good ideas. Whatever comes next, it cannot be a simple restoration of the same comfortable liberalism that produced two Trump terms and the genocide of the Palestinian people.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about fictional teenage girls beating the shit out of each other.

Rita Bullwinkel plays with her food

Bullwinkel’s 2024 debut novel Headshot tracks the course of the fictional Daughters of America boxing tournament in Reno, Nevada. There are eight major perspective characters—the girls—and each fight is told as a competition between the girls to which each brings her neuroses and past obsessions. Through the fight and interstitial moments we get glimpses of the girl’s home lives and futures. For most of them this tournament carries a lot of immediate emotional weight, but will eventually be forgotten.

I liked the juxtaposition of the immediate importance of the fights with their conscious insignificance in the girls’ future lives. Bullwinkel shows these moments are points of real inflexion, but that inflexion itself is often forgotten later, or simply the emergence of buried psychological elements.

But there’s also a weird, interesting thing going on with food and defeat in the boxing ring. Generally, Bullwinkel uses food comparisons when a person’s body is about to fail, or is otherwise marked as mortal/defective. Bullwinkel avoids mentioning food much at all unless it’s in association with the failure of a body part or with death. One girl, Andi Taylor, is a lifeguard on the weekends. Recently a child wearing a red-truck swimming suit drowned during one of of Andi’s shifts. She can’t stop thinking about him. And she can’t stop thinking about food.

We start with Andi Taylor’s dead red-truck kid: “It was the image of his small, corn-dog-sized thigh that made her vomit.” (15) Throughout the Artemis Victor v. Andi Taylor section, Andi returns again and again to the corn-dog thigh. This image is part of a set of associations that cause her to lose focus and contribute to Artemis’ victory. Later in the bout, Artemis lines up a square shot on Andi: “Andi’s nose bleeding. Andi’s nose feeling like cornflakes…Andi had recklessly killed that red-truck kid at the crowded community pool…Where was the babysitter when the Kid’s corn-dog leg went from alive to dead?” (29). This connection of bodily trauma to food is doubled here. I love the intensity of the cornflake image, it’s gross and strange and obviously painful. And the run of association from that image to the repetition of the dead kid corn-dog comparison reinforced the association between Andi’s own feelings of failure and food. This hit turns out to be the turning point in the match, from this moment on Andi largely loses control of the fight and retreats into her memories of the boy’s death.

Andi’s inability to save the kid is also tied to food. While the kid was drowning: “She had been eating an apple while looking across the pool, over the roof of the snack stand.” (36) For Andi, other images, notably the color blue, are also associated with death. But food is uniquely tied to failure—to swim, to block, to live. Her father, who is dead, is said to have described her arms as “tentacles, because she was always grabbing for candy,” (42). On the next page, Andi imagines the dead kid’s vocabulary fitting into a lunchbox and she imagines the babysitter leaving this lunchbox at home, having to buy another lunch.

The link between food and bodily death/failure is particularly tight in Andi’s section, where it is one of the clearest throughlines. I think what is happening here and what seems to happen through most of the book, is that Bullwinkel is constructing an argument where the mental superiority of the boxer’s inner-world is the important factor in determining the fight.

Andi’s mind strays, she loses her targets, when she’s hit her head gets fuzzy. She lacks a coherent theory of victory—which Artemis and Rachel Doricko both possess, for instance. In Headshot girls don’t necessarily win because they are stronger or because they can hit harder, but because they remain in control of their inner lives. This control allows for a tight integration of conscious perspective with bodily experience: the perceptual apparatus works almost automatically for the good fighters. They see holes in their opponents stances and punch almost without thought. But as the control is loosened, the primacy of the body as a desiring/physical thing reasserts itself. Food plays an important role in this process because eating is such an embodied experience. A being of pure mind cannot feel like corn-flakes, cannot conceptualize another’s body as a corn-dog or be labeled as something reaching for candy.

The repetition of food images as signal of emotional weakness and incapacity in combat extends to the second fight, where Rachel Doricko, who has a theory of boxing she calls Weird Hat theory, defeats Kate Heffer, the obsessive counter. The decisive moment of the Doricko-Heffer fight is another food-linked headshot. Rachel hits Kate hard enough that her eye bleeds and swells:

Here she is now, being beat badly, with a puffed-out bloody eye that makes her look like her body is a single-use, disposable paper plate, and that the paper plate of Kate’s body has been used for a barbecue where there is a lot of ketchup so that the ketchup has been dribbled all over the paper plate of Kate’s face to such an extent that the plate is soggy and almost unrecognizable and most certainly no longer of use. (78)

The length of the sentence, eighty words, calls attention to the significance of the images: the disposability of the plate, the ketchup-y redness of the blood, how messy it all is. This is a much clearer example of the body-food physicality linkage. Kate’s fall from fighter to loser produces the same beaten body as food phenomenon as Andi’s nose. She is reduced to an inanimate phenomenon, to be toyed with and consumed by a more skilled, more controlled fighter. It’s no coincidence that Rachel chews on the tail of her Daniel Boone hat to intimidate opponents like Kate. Rachel plays with her food. But the reduction to an object of consumption also frees Kate from concentrating on the fight, she no longer has to count in her head, she’s freed to come to the realization that she is not the protagonist of reality.

There is a seeming exception to the food-defeat connection in Rachel Doricko, who wins so convincingly against Kate and later against Artemis Victor. Rachel is routinely described as resembling “pounded-veal,” (77) while knocking the hell out of her opponents. And we get a scene of her eating during the lunch break on the first day of the tournament: “The sugar from the orange tastes incredible. Rachel wonders if it would be possible to pump herself full of orange juice intravenously. She’d love to have this orange go straight from her blood into her veal cutlet.” (81).

But when Rachel loses the first two rounds of her second fight to Artemis, we get the pounded veal cutlet image again, while Artemis’ body is compared to “a toned cut of meat.” (162). Artemis is defeated. And while the veal cutlet image is not again repeated in Rachel’s final fight, against Rose Mueller, we’ve gotten enough of it to associate her with food. She too, is defeated, though less decisively than the others. But again, this fight comes down to a mental contest, rather than a bodily one: “Boxing against Rose Mueller felt like fighting someone who was telepathic. She knew where my fists were going to go before my punches even landed,” (201) Rachel thinks to herself. This is a callback to Rose’s theory that bullied children become softly telepathic, another assertion of the primacy of the internal world over and against the external.

But what does all this mean?

That Rachel Doricko is foreshadowed as the loser is interesting, in part because Rachel was my favorite character. I found her Weird Hat theory, which posits that it pays in a competition to be off-putting, difficult to understand and odd, quite charming. Rose Mueller, though, is less dynamic, less charming, more normal. So her victory, the victory of a bourgeois woman who prays and eventually will become a small business owner in the Texas suburbs, is something of a reification of types of femininity at odds with the refuge that the boxing ring offers to the weird and the alienated.

Headshot is written in a vaguely timeless moment—it’s not 2025 and it’s not 1965, but somewhere between those. I found myself thinking of Fighting in the Age of Loneliness, an uneven 2018 documentary by sports commentator Jon Bois and podcaster Felix Biederman about the connection between cultural alienation and combat sports. “People who have been flattened by the earth still live, even if they feel they don’t fit in anywhere, and of course, one place was tailor-made in our culture for people who did not fit,” Biederman said of the attraction that combat sports, particularly MMA, held for many victims of the ‘08-10 recession. The boxing ring, the reduction to ketchup and pounded veal, literalizes the alienation that Andi Taylor and Rachel Doricko and Kate Heffer feel. Their loneliness becomes a physical process in the ring.

But the frailty of the body in combat stands in odd-juxtaposition with the final couple pages, where Bullwinkel zooms out to a speculative, interplanetary future where two girls fight under the light of alien stars, over the rules of a hand-clapping game. There’s an almost biological essentialism at play in these last pages; defined by ovaries and by reproductive capacity (“Tiny future fighters are nested inside the infant bodies of baby girls. Men are dead ends.” (205)), Bullwinkel’s girl fighters do not get an easy way out of the problems of patriarchal domination. They fight as young women, then never again. To me, this speculative element was the weakest part of the novel—not just because I think interplanetary space travel is pretty much impossible and I don’t think industrial civilization will survive the next hundred years—but because it recuperates the violence and the uneasiness of the tournament into an almost-saccharine girlhood. There’s a dynamic tension in the fleetingness of these girls’ boxing careers and the rest of their lives, which Bullwinkel goes to great lengths to explain. But the cosmic extrapolation misses the emotional intensity that specific lives give to a text.

It feels like the last bite of an otherwise tasty corn-dog, a little soggy, a little too much cornmeal.

I also read:

For school: George Saunders, the Art of Fiction No. 245, the Paris Review. A very good interview.

Next Week: Rachel Cusk’s Second Place. Probably.

-30-

*for more on why I’m a little burned out on political organizing, read this essay.

I did find you through the tik tok you mentioned but I'm also a fellow Creative Writing graduate (just passed my PhD subject to minor amendments) so actually even happier than I was initially! Looking forward to catching up on your work!

One of the new subscribers. Thank you 🫶 Your words are prescient and the clarity is appreciated.